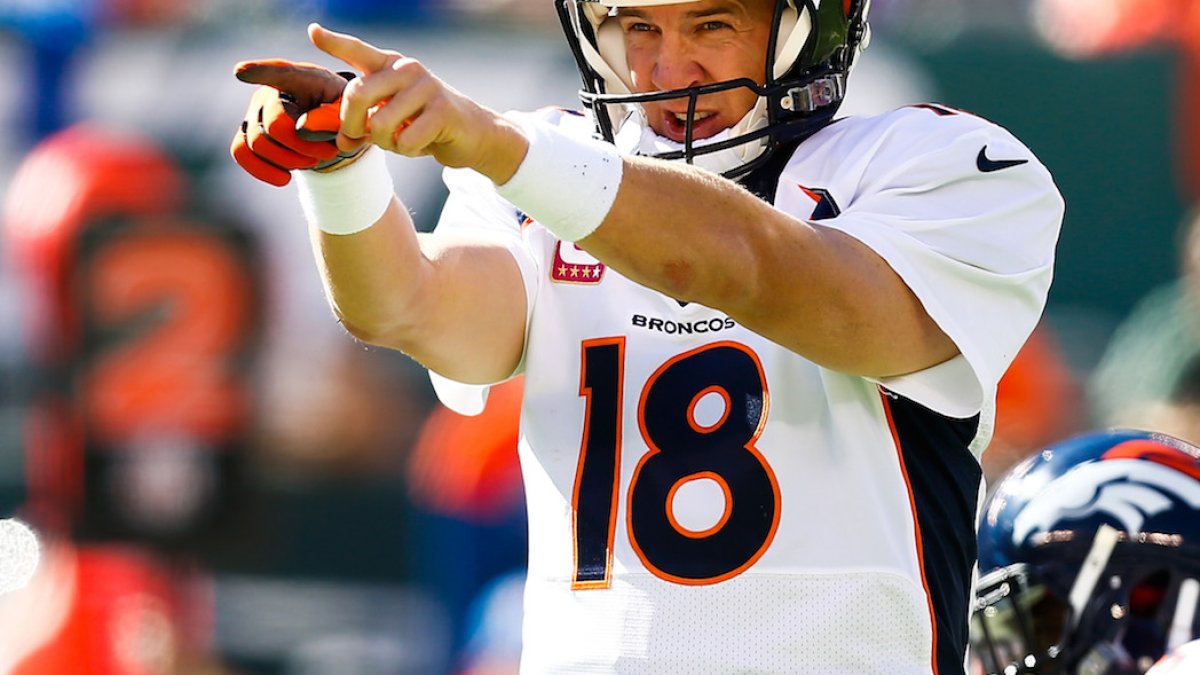

Peyton Manning will officially walk away from the NFL today after 18 seasons in which he re-wrote the passing record books, re-defined what a modern quarterback should look like, and ultimately ended a successful chase for a second championship ring with his final go around.

Manning’s legacy will remain in flux for some time to come, and there will be much written about it (for better or worse), but here we are going to look at his career in the light of the time PFF has been grading.

PFF has full years of grading dating back to the 2007 season, Manning’s 10th in the league, and we have graded every snap he has taken over the final nine years of his career (only eight of which he actually played in).

Over that span, he led the PFF quarterback rankings on four separate occasions, grading out as the best QB in the league in half of the seasons he actually suited up for over the PFF era.

That isn’t to say that Manning is necessarily the best quarterback over those years, something which is an extremely subjective title to throw on a player. Looking at cumulative overall PFF grade alone over that period, Manning can’t match Drew Brees, who has the best cumulative grade of any QB over that span.

Aaron Rodgers or Tom Brady, each of whom have also missed a year (Rodgers because of Favre starting in 2007, and Brady to injury in 2008), both also have Manning beat in cumulative overall grade, though Manning tops Brady when looking at passing grade alone.

While each of the three has Manning beat in cumulative overall grade over the PFF era, none of them has led the league more than once, while Manning has done so four times.

Enough will be written about the cumulative numbers of Manning’s career, so instead, let’s use the PFF numbers to quantify the kind of quarterback he was. In each of the last three seasons Manning has averaged less time with the ball in his hands than any other QB in football. In 2015, he averaged just 2.31 seconds each dropback, which is almost a full second less on every single passing play than Russell Wilson at the other end of the scale.

We all know about Manning’s pre-snap theatrics and pantomime, but it always served a very real purpose—allowing him to diagnose and understand what he was facing to get the offense in the right play at the right time, with minimal post-snap processing involved. His game was never about delivering the low-percentage heave down field that results in a score, but about playing the percentages and taking the right option—even just knowing what the right option was every play.

That can be seen in other PFF numbers, as well. The speed with which Manning is able to get rid of the football has always meant that he helps out his pass protection more than maybe any other passer. Going back to players like Tony Ugoh and beyond, Manning has always played behind blockers that would be seen as huge problems for most other quarterbacks, but were rendered minor inconveniences by his quick release.

In the past six seasons of Manning's play, he hasn’t been higher than 27th in the NFL in terms of the percentage of dropbacks he was pressured. He has been very rarely pressured, and it hasn’t been because his teams have had the best pass-protecting units in football—in fact, only once over the PFF era has that been true in grading terms (the 2012 Broncos). Manning’s pre-snap work, which allows the ball to come out so quickly, also means that it’s tougher to pressure him. This past season represented the greatest percentage of dropbacks that he felt pressure, at 34.0 percent, and that is still some way shy of Teddy Bridgewater, who felt heat on a ridiculous 46.9 percent of dropbacks to lead the league.

Even if a team did manage to pressure Manning, it was another matter getting him to the ground and converting the pressure into a sack. Since we have been grading, the worst Manning has been league-wide in allowing pressure to be converted to sacks is 12th out of around 45 passers each season. He has been the most difficult quarterback to convert pressure against, and in the top three statistically in four out of his eight seasons during the PFF era.

Manning’s game wasn’t just about knowing where he should be going with the football pre-snap, but he always knew where his check-down option was, and he is maybe the best quarterback over that time at being able to mitigate pressure and turn bad plays into good, simply by getting rid of the ball and understanding when a better option isn't going to develop.

In fact, when you look at his career over the PFF era—a career of two parts and spanning two franchises—the thing that stands out, fittingly given Manning’s reputation, is his work mentally as a quarterback.

By the end of his days in Indianapolis, he was carrying almost the same old team to the playoffs every year, and nothing was changing. It wasn’t that the Colts were necessarily a bad side, but more that they just didn’t change anything year to year, expecting that Manning would ultimately get them over the hump again as he had in 2006 and so nearly did in 2009. Manning’s performances in Indianapolis had become almost routine. We expected him to be great and he never had any new challenges to deal with—but that changed almost immediately in Denver.

His 2011 season was lost due to neck surgery, and there was a very real feeling that he would never be able to return to play. When reports first surfaced about how bad his arm was when he started his comeback rehab, it looked like we had seen the last of him, but he ultimately got himself back in good enough shape to be signed by the Denver Broncos, hoping Manning could get them back to the Super Bowl.

His first game back was an excellent performance, but one in which he attempted just one deep (20+ air yards) pass, and missed. His second game came against Atlanta and featured three first-half interceptions deep down the middle of the field on almost the same play—a play that had been one of Manning’s go-to weapons in Indy, and one which he had to accept he no longer had the arm to use.

This game showed Manning that, if he wanted to succeed in Denver, he needed to completely alter his game based on what he now had the physical capability to achieve, and not what he had been able to do in the past. Seam routes down the middle that he had used to carve up zone coverage for years were now almost entirely off the table—he just didn’t have the arm strength to make the throw anymore—but he could still play to his strengths and put the ball where it needed to go more often than virtually any other passer in the league. Those first two seasons in Denver saw Manning post an accuracy rate of 78.0 percent and 77.3 percent, the best two figures of Manning’s career during the PFF era.

To make that big of an adjustment to your game as an NFL QB is incredible in abstract terms. To do so after 13 years of play, and 14 years of mental reps after just a couple of games back from injury, and then post arguably the best seasons of your career, almost defies belief.

Manning’s cerebral mastery and mental excellence shouldn’t be represented by the number of touchdowns he finished his career with (539), or the number of yards (71,940), the completion percentage he posted over eighteen years (65.3 percent), or the passer rating (96.5). That mental ability should be illustrated by having the self-discipline to re-learn the position almost 15 years into his career, at a time when most players would have been stubbornly clinging on to what got them that far.

Manning succeeded in Denver and ultimately secured himself and the franchise another ring because he was both prepared and able to adapt his game to new and pronounced physical shortcomings. He was able to lean on what he had always been good at, and take certain throws almost entirely off the table because he saw quickly that they simply were no longer options for him. Manning posted All-Pro seasons with physical tools that would have been seen as undraftable had he been a prospect coming into the league fresh in any of those seasons.

Though it’s true in pure grading terms that other quarterbacks have posted higher figures since PFF has been grading, it may also be true that we haven’t seen a feat from another quarterback more impressive than that change from Manning.

We aren’t just seeing the last of a quarterback who leaves the league with most of the major passing records in his name, but a player who has topped the PFF rankings more than any other passer, and reinvented his game in a way rarely asked of players. The fact he was able to succeed and go out on top should be a very real part of his legacy as a player.

© 2024 PFF - all rights reserved.

© 2024 PFF - all rights reserved.